Offset Loading- A Comprehensive Introduction

- Danny Foley- MS, CSCS,D*

- Jun 2, 2019

- 11 min read

Updated: May 15, 2020

I wanted to reignite my article writing by setting the template for what will be my predominant focus throughout the coming summer months- offset loading, sling and vector training, and unbalanced/unilateral work. If you’ve been following me on social media over the last few months, you’ve likely noticed that I’ve been flirting with these concepts in a variety of ways. Well, after about six months of anecdotal “experimental trials”, I’ve reached a point where I am overwhelmingly convinced that there is something to this offset loading and vector-specific training; although candidly, I’m still not exactly sure what that “something” is, or how to fully articulate it, yet. But with that, my short-term goal has become to not only disseminate everything I can on the subjects, but to validate them with some lab work and hopefully get a couple studies published on these topics.

I’ll be doing independent articles for each of the aforementioned topics over the course of the next few weeks. But for today, I would like to start with offset loading. Because this concept, along with some of the others, is quite different for most athletes/coaches, I need to preface this article with a ‘CYA’ disclaimer. The material to follow throughout this article is based EXCLUSIVELY off of anecdotal evidence/trial & error. I have not yet been able to find anything scholarly to validate my beliefs with regard to offset loading, and I know that this is seldomly practiced in most strength training facilities. That being said, if this is something you feel would benefit your training, or something you would have interest in sampling, please use precaution with loading and execution. I will do my best to be thorough in my suggestions and guidelines for those who have never performed offset loading, but without being physically present it is difficult to generalize instruction. Therefore, anyone who applies the material in this article is acknowledging that they assume any potential risk of injury.

What is offset loading:

Just as it’s described, offset loading is taking any conventional barbell movement and intentionally loading the barbell differently on each side. Offset loading can also be applied by using uneven dumbbells/kettlebells (i.e. 40 lbs. in one hand and 20 lbs. in the other) while performing any given movement. Additionally, this can be applied using accommodating resistance tools such as bands or chains, whereby only one side of the barbell has bands/chains added to the static mass. Here's a link for more examples of offset loading. OFFSET LOAD COMPILATION

How is this different than standard loading…?

I view this offset loading (particularly when using a barbell) as a blend of conventional bilateral and unilateral loading. Think about doing a good ol’ fashioned barbell bench press, now think about doing a single-arm dumbbell bench press. With an offset barbell bench press, I feel like we’re getting a blend of both methods, in which one side is going to be stressed slightly more than the other, but the opposite side musculature is still involved. This goes for virtually any conventional movement you can think of, no matter the movement this principle is applied.

More specifically, I feel this offset loading targets what are known as the fascial slings that I spoke about in relatively lengthy detail in my recent eBook publication Conscious Core. Fascia is a biological fabric that acts as a swath enveloping every single muscle in the human body via a singular interwoven sheath. To elucidate this a bit, Thomas Meyers, the pioneer of all things Fascia and founder of Anatomy Trains, argues the question “do we really have 600 muscles in the body, or one muscle with 600 fascia pockets?” Throughout the body, the fascia is distributed in varying amounts, meaning there are certain regions that possess more or less fascia density than others. An easy example of this that most should be familiar to is the IT band. The IT band is one of the most highly concentrated fascia regions found in the body, which is why it is seemingly impossible to treat the IT band with conventional therapeutic methods. Fascia is a highly unique structure, and in some regard, is still largely unknown. But from what we do already know, we can ascertain that fascia has similar pliability to muscle, but also has the tensile strength of steel. To put it in as simple terms as I can, just think of your fascial system as an enormous rubber band that acts as a spring to propel movement. These rubber bands have varying tension and elastic properties and are also positioned at varying angles throughout the body.

But speaking back to the slings… these slings run in diagonal, helical patterns across the torso and then down the lower kinetic chain. So from one shoulder to the opposite hip, both anteriorly and posteriorly, we have powerful fascial slings that are involved in just about any biomechanical action. Fascia is fundamentally paramount for force management, as it is involved in generating, managing, and distributing forces throughout the body (Parisi, B. & Allen, J., 2018). Your fascial tension is also a major contributor to resting and active posture, preserving the spine from deforming and possibly even an electrical conduit for neuromuscular transmission (Parisi, B. & Allen, J., 2018). It's highly important to understand that these helical structures are encircled throughout the body, but also, how that should be considered in exercise selection and programming. Take a look below:

So, how exactly does offset loading promote these fascial structures? Well, again I don’t have any formal evidence to validate this, so if you’re one of those “show me the research” people then allow me to recommend you not waste any more time reading this article. But for the rest of you, I believe this is linked to the direction in which the fascia slings run, along with the angle at which they are positioned. Furthermore, I believe that by off-setting the load we are changing the bracing (or stabilizing) mechanics predominantly centric to the core, as well as altering the firing sequence of muscular activation. In doing so, if NOTHING else, we are simply changing the responsibility of the working musculature, the timing of muscular contraction, and altering the role(s) of synergist muscles. Collectively, this fundamentally changes the kinematics of the movement, as compared to doing the same exact movement with standard, bilateral loading.

I would also argue that the force vectors are also altered during offset loading movement patterns. Because we’re performing the movements in the exact same fashion as we would with conventional load, I believe the modified, unbalanced weight distribution creates diagonal force vectors that again change the kinematic sequence of movement execution. Much of the time, these additional force vectors, namely the diagonal forces, are recruiting musculature that just isn’t activated during standard loading. A good example of this is when I was playing around with static offset overhead holds, using a barbell with a 25 lbs. plate on one side, and nothing on the opposite side.

When I do this exercise, and the weighted side is on my right, I feel this working my contralateral (left side) QL. For reference, if doing a static overhead hold with a balanced barbell, I would feel this mostly in my traps, lats, and anterior core. But when there is only a single plate on one side of the barbell, I feel virtually nothing in those regions, and almost exclusively in that opposite side QL. To add another example to this, let’s use the bent row, conventional loading versus offset loading. When I do a conventionally loaded barbell bent row, as most should, I predominantly feel it in my upper-mid back, some glute, and hamstrings. When using the offset load, I feel it predominantly in my contralateral abdomen primarily, upper-mid back and hamstrings secondarily. Again, these comparisons are being drawn with the same absolute or total load, so even though we may not yet be capable of drawing a definitive conclusion as to why, I can assure you, there is something different about this load application.

Biotensegrity:

Biotensegrity is a term I (somewhat embarrassingly) only recently came across a few months back. But ever since being introduced to this term, I have become obsessive in understanding everything I can about it. At its root, biotensegrity is a descriptive term of how the body (‘bio’) creates and maintains tension (‘tensegrity’) while generating movement. In a nut shell, biotensegrity opposes what we’ve all been led to believe is the underpinning to human movement, that being conventional Newtonian physics. Without getting too nerdy on you, Newtonian physics suggests that all human movement is a result of coordinated interaction between numerous levers (bones) and pullies (musculotendon complex) that collectively provide us the ability to move.

Conversely, the concept behind biotensegrity is that there are only two mechanical systems at play with regard to human movement- tension and compression. Now, I’m far from an engineer, and will never pretend to be, the finite details and intricacies to a lot of this shit is still green for me. But thankfully, we have this magical thing known as the internet, so allow me to give you a far more comprehensive overview from a gentleman named Dr. Stephen Levin on biotensegrity. Levin describes this concept as “There are no shears, bending moments or levers, just simple tension and compression, in a self-organizing, hierarchical, load distributing, low energy consuming structure."

If I can summarize all that in a succinct manner, another good way of thinking of human movement is that “everything effects everything”. We must do all we can to distance ourselves from the archaic belief that the human system works by way of levers and pullies and begin to supplant this with the concepts of biotensegrity- “just simple tension and compression.”

How I utilize offset loading:

First let me be explicitly clear on this… I only use offset loading as a piece of the puzzle. By no means am I suggesting you do away with conventional lifts or standard bilateral loading. By no means am I suggesting that this offset loading should be the forefront of your training. What I am saying, however, is that in my opinion it most certainly has a place, and when utilized correctly can have tremendous benefits on your athletes. I do my best to avoid generalizing, but just to provide some context here, I would say that offset loading accounts for roughly 10-20% of my training, of course depending on the athlete I’m working with. For some of my advanced athletes and special populations, this may grow to 25-40% of my total training. Before I get a little deeper into how I’m using this with my athletes, let me offer a few broad, general suggestions for initiating this:

-Before doing anything with a barbell, I would recommend using uneven dumbbells/kettlebells first. This tends to be easier on the athlete, and easier for them to grasp the concept.

-Both the total load and difference in load will inherently be subject specific, first, and movement specific second. It’s difficult to give a sweeping recommendation on where to start because of this, but when using uneven DBs/KBs, I would recommend staying within a 10-20 lbs. margin between sides. Here's a short list of good candidates for an intro to sampling offset loading:

1.) Farmers carries

2.) RDL’s

3.) Bent rows

4.) Lunges/step-ups

-It’s extremely important to understand that the technique and execution of movement should be coached and performed no differently than that same movement with standard loading. The objective is always to keep the bar (or bells) as parallel to the ground as possible, and to not favor one side or the other irrespective of the load.

-Additionally, you will always train the movement on both sides. Meaning you will always perform equal reps on both sides with the unbalanced load.

-Once you progress to a barbell, the instructions are the same as outlined above. Once your body becomes more accustomed to this type of loading, you can now venture into including more movements. Here are a few I would suggest sampling first when using a barbell:

1.) Overhead press and carries

2.) Back squat

3.) Goodmornings

4.) Bench press

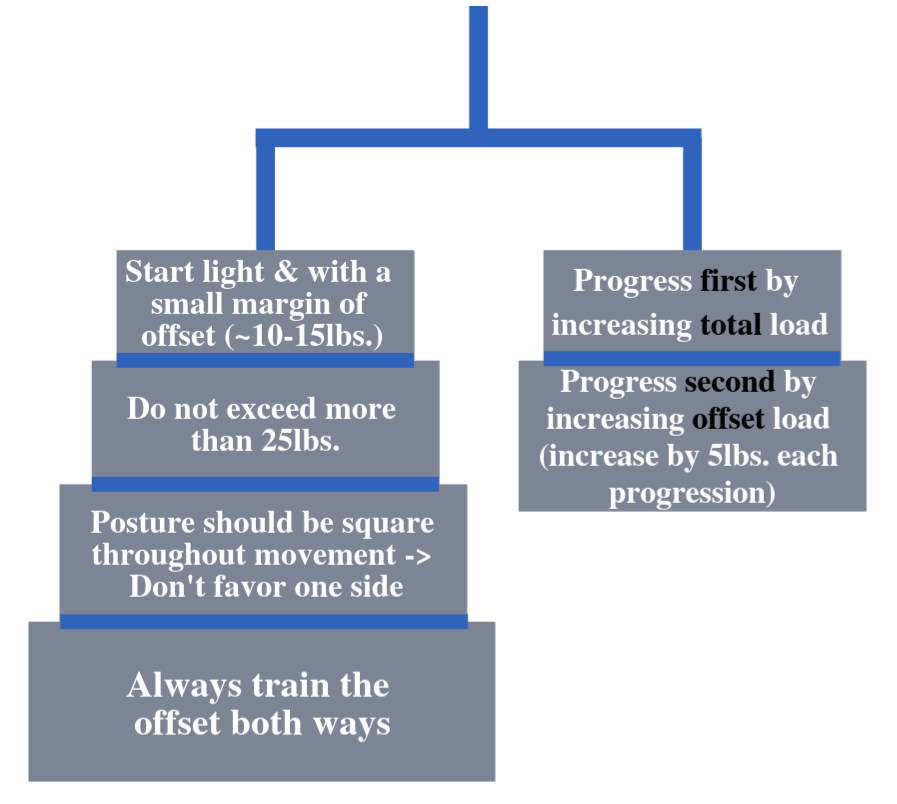

-It is also difficult to transcribe the offset work to conventional intensity parameters (i.e. %1-RM). My advice is to start with very light absolute weight and a small margin of offset (i.e. 5-10 lbs.). I would never use this with any heavy loading, so for all intents and purposes, think <50% 1-RM.

-Always increase the TOTAL load FIRST and the margin between sides SECOND. I would also recommend using 5 lbs. increments for progressing the offset, and never go above 25 lbs.

By now, it should hardly be a secret that I put an absolute premium on core training. With the offset loading, irrespective of the exercise, the core is exactly what is at the forefront of my mind and intent. I suppose the global purpose of the offset loading is to strengthen the functional core while performing a variety of movements. This would also be an opportune time to remind you that not only is the core centric to everything we do, but it is also more important to emphasize synergistic strength of the core rather than simply in isolated fashion. Another way I like to think about it is we need to directly train the core, while not directly training it. What this means is that the core must be considered and coached with damn near any movement you have your athletes doing. While performing the offset loading, we are achieving precisely that by changing the stability requirements at the torso, while training other muscles. Call it specificity, call it functional… frankly I’m far less concerned with which subcategory this would be classified under, my focus is simply on optimizing the athlete.

Sample Training Day and Programming:

So we’ve already established that this only accounts for a fraction of my training. I feel this is something that gets egregiously misconstrued on social media platforms but is extremely important to understand. Offset loading is merely a tool in the toolbox, it is not meant to replace or supplant anything. It is an additive training method that, for the right population, is a progressive means for creating a new stimulus for the athlete. Yes, we still use conventional, bilateral loading, and no, this isn’t some mystical “secret to untapped potential”. Think of it no differently than concerted mobility/flexibility methods, plyometrics, or “functional” training variations- not the end all be all, but a valid alternative to sample in your training in some capacity depending on need and ability.

I use the block method for my programming, it’s just what has always made sense to me. This, I believe, is widely practiced, well-understood, and as far as I’ve known- effective. Broadly speaking, my Block 1 is reserved for my primary lifts (i.e. bench press, back squat, deadlift, hang clean). I will normally perform my primary lifts in isolation, or pair them with something non-competing/non-fatiguing (either soft tissue or mobility work). My Block 2 is where I usually perform compound accessories (i.e. landmine presses, various SL squats, high pulls, etc.). Typically, this will consist of 2-3 exercises. My Block 3 is where I place my isolated accessories (i.e. triceps variations, single-joint pulls, hamstring variations, etc.). Since I’ve started incorporating the offset loading, I have programmed this for both Block 2 and/or Block 3. Here’s an example to provide some context:

As you can see, it’s only a marginal shift in exercise selection, and the offset work is only a fraction of what I’m doing. That being said, this minimal adjustment has made enormous differences in my training outcomes, which I’ve now applied to several of my athletes with a wide spectrum of abilities/training goals.

In Closing:

Look, I may be on to something with this, but there’s an equal possibility that this has little-to-no effect at all. It may be population specific, or it may not be. Quite frankly, there’s a lot to this offset theory that has just yet to be defined, so the best I can do is evaluate objectively and use good discretion to make educated decisions. But as I’ve been promoting heavily throughout this article, I am personally convinced that this is not only a prudent addition to your training but may have greater ramifications than myself or others are presently aware of. Let me also clear another thing up- in no way shape or form am I looking to be acknowledged as discovering offset loading. As with most strength training methods, I’m sure it’s been utilized in select realms over the decades of strength evolution and has just never been glorified. But to my knowledge, I have only seen two other coaches ever utilize this with their athletes- Andrea Hudy, the Head Strength Coach for Kansas basketball and also one of the most widely respected and influential strength coaches in the industry today. And Dr. Joel Seedman, who has an enormous social media following and is constantly putting out exceptional content. I steal so much from Joel that I should probably be invoiced. So, if this can serve as some kind of backing, I’ll say this much, if these two, who are waaayyy smarter than me are using offset loading, I can’t be too far out there with my thoughts on the matter.

Hopefully you were able to take something from this write-up, as I continue to navigate this mode of training, I will continue to publish articles on what I’ve noticed from it. Moreover, I will be doing all that I can to get someone to conduct a formal study with offset loading over the summer. Again, I don’t know if this is truly effective or smoke in mirrors until we can look at some data, but until then, give offset loading a trial in your training. If you’re a coach, please be sure to try these methods out for yourself first before having your athletes do anything. And if you’re someone with a significant injury history, especially spinal injury history, please use caution. As always, I’m available via email anytime to help guide you through sampling offset training if you feel it’s warranted.

Comments